If you’ve practiced capturing energy in the previous tutorial, you’ll have acquired a good feel for loose sketching of people. We’re going to start giving structure to that feeling-based groundwork by studying the body with a more scientific eye.

Let me say that it will take many sessions to cover the wonders of the human body. Not only is it among the most sophisticated animal structures in nature, it is also one of those with most variations: few other species come in so many shapes and colors. Nobody, therefore, should feel frustrated for having trouble drawing people; it is an ambitious undertaking.

We’re going to build up this skill from the ground up, in the same order as a drawing process, starting with a simplified skeleton (the basic figure or stick figure), moving on to the volumes of muscle structure, and then finally the details of each part of the body and face.

The first fundamental to acquire is proportions, and we’re going to be practicing with this basic figure for a while while we become familiar, not only with the conventional "ideal proportions", but also with the way they vary with gender, age, even ethnic background.

If you're drawing digitally, perhaps you want your work to look more like it's created with pencil and paper. If this is the case, may we recommend one of the many Photoshop brush sets available on GraphicRiver, including this Classic Art Brush Pack.

The Basic Figure

Create Your Chart From Heads

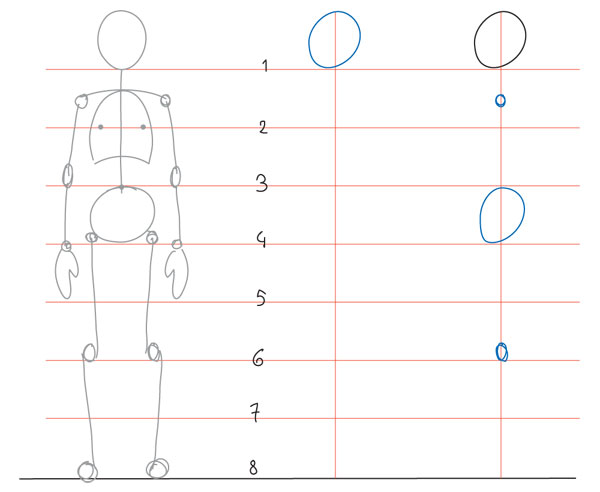

A well-proportioned figure, regardless of variations due to gender or such, is defined by the alignment of the joints, which is invariable (that is, we perceive something odd if it does vary). This is our groundwork for proportions. Draw your own chart with me as we go, it really helps learning the material.

Start by drawing an oval or egg shape (pointy end down) for a head, and mark down eight measurements, the last one being the ground.

The measurement (ideal male height = eight heads) was set down during the Renaissance as an idealization of the human form. It’s rather obvious that very few people are actually eight heads tall (even Northern Europeans, who served as basis for this model, are closer to seven heads), but this is still the best model to start with, as it makes it easier to grasp the alignments.

The Pelvis

Add the pelvic bone next, simplified as a flattened circle between marks 3 and 4, with the hip joints sitting on 4. Its width is roughly 1.5 to 2 head-widths. You can now draw the spine connecting the head to this most important part of the body, its center of gravity and stability.

The Legs and Knees

Let’s assume this figure is standing with feet vertically aligned with the hip joints. The knee joints sit on mark 6, as that line corresponds to the bottom of the knee caps.

When the leg is stretched out, the knee joint is placed on a straight line with the hip and ankle (left). But this straight line is virtual: to complete the leg, connect the hip joint to the inside of the knee cap, and then again, the outside of the knee to the inside of the ankle (right). This is a very simplified but accurate representation of the actual bone structure, and helps in drawing the natural look of the human leg, which tapers in from the hip, then staggers out at the knee and tapers in again. It also helps with placing the muscles at a later stage.

The Ribcage, Nipples and Belly Button

The ribcage-lungs group is the third important volume of the body, after the head and the pelvis. Simplified, it is an oval that starts halfway between 1 and 2, down to mark 3; but it is best to chop off the lower part of it as shown here to imitate the actual rib cage, as the empty part between the two volumes is important: it is soft and subject to change (flat belly, soft belly, wasp waist) and it is also where the most torsion and movement happens in the spine. It’s good to be aware of that and not attach torso and pelvis together like two blocks, as that would "block" your drawing’s range of motion. The width of the oval is roughly the same as the pelvis for now.

Two more details here: the nipples fall on mark 2, just inside the sides of the head, and the belly button on mark 3.

The Shoulders

The shoulder line is about halfway between marks 1 and 2, with the shoulder width 2 to 3 head-widths, but its apparent position can vary a great deal. To begin with, it’s slightly curved down, but in tension the shoulders tense up and the curve can itself turn up and look higher. Furthermore, the trapezius muscle, which from the front appears to connect the shoulder with the neck, is highly individual; if it’s very muscular, or carries much fat, it can make the shoulder line look so high there’s no neck; inversely, an underdeveloped trapezius, often seen in very young women, gives the impression of a long neck.

This brief digression into non-skeletal details is to insure there is no confusion between the actual position of the shoulder line and its apparent placement in a fleshed-out body, some examples of which are shown below.

The Arm, Wrists and Hands

Finally, the arms: The wrists are on mark 4, slightly below the hip joints which sit on it (you can test it out for yourself by standing up and pressing your wrists against your hips). The fingers end roughly at mid-thigh, which is mark 5. The elbows are a slightly complicated joint that we’ll examine in detail later, but for now it’s helpful to mark them as elongated ovals sitting on level 3.

We’re done... almost. Before summing this up, let’s extend those marks into lines and see how this works in profile.

The Basic Profile

Start by drawing the head again, the same egg shape but with the end pointing diagonally down, and drop a vertical line from the crown to the ground.

In an erect posture, you can place the pelvic bone (a narrower version of the head’s egg), the shoulder and knee roughly on this vertical line. They are on the same level as before: all the joints are, but the others are not on the same plane as these.

The Spine in Profile

From the side, the spine is revealed as being shaped like a flattened "S". From the base of the skull, it moves down and back till it reaches its furthest point at the level of the shoulders (between the shoulder blades). Note the shoulder joints are ahead of the spine! This is because, again, the shoulder "line" is in reality an arc: the medallion shows a top view of it.

The spine then comes back forward, and peaks again (inward) a little above the pelvis (the small of the back, which varies in depth and can make for arched back). Finally it changes direction again briefly and ends in the coccyx or tail bone.

The Ribcage and Legs in Profile

The ribcage is closely attached to the spine, and, in a reasonably fit body standing erect, the chest is naturally pushed forward.

The hip joint is ahead of our vertical axis, and this is counterbalanced by the ankle being a bit behind it. So our hip-knee-ankle line is slanted backward, and staggered again: from hip joint to front of knee joint, and from back of knee joint to ankle.

The overall effect of this posture is a visual arc from head to chest to feet (in green), and when it’s flattened or reversed, we perceive an uncertainty or slouch in the posture.

The Arms in Profile

Finally, the arms. The upper arm falls fairly straight from the shoulder, so the elbow can be aligned with the latter (or fall slightly backward). But the arm is never fully stretched when at rest, so the forearm is not vertical: the arm is slightly bend and the wrist falls forward, right over the hip bone. (Also when the hand is relaxed, fingers curl a little as shown here).

To Sum Up

This completes the basic, undifferentiated human proportions, and here’s a diagram to sum up all of the above:

Proportion Reminders

The following are a few useful visual reminders that are based in the body. They come in handy when the body is not standing upright.

Advertisement

Practice Time

We’ve covered a lot of material, and now is a good time to pause the studying and familiarize yourself with this basic figure before we move on to differences between male and female structures (and others). For instance, you can integrate this new knowledge to your daily sketching practice by overlaying a quick energy sketch with this correctly proportioned basic figure.

A Few Tips

I consistently start with the head, but it doesn’t really matter what part of the body you start drawing, if you’re comfortable and get a good result. If unsure or are having a hard time, then I do suggest trying with the head first.

Get used to drawing this basic figure with a light hand, since the finished body will be built up over it. Traditionally, the final lines are inked and the guidelines then erased (hence the importance of a light hand) but even when I’m sketching with a ballpoint in the intent of inking on a different sheet by transparency, keeping a light hand ensures I can see what I’m doing.

Advertisement

No comments:

Post a Comment